Making compliance everyones business through simplified, ubiquitous and transparent adoption

Leonor Ciarlone, Senior Analyst, The Gilbane Group, November 2006

Sponsored by Omtool

Compliance regulations challenge organizations across multiple industries to reengineer business processes. While the focus has been primarily on electronic business processes and communications, corporate and compliance mandates are extending to paper-based processes. It is not uncommon for compliance officers and corporate legal departments to struggle with transforming strategy into reality. Despite efforts, many organizations experience costly, disruptive, and fragmented program implementations that often go underutilized. This paper discusses how creating a “culture of compliance” demystifies and distributes program adoption by integrating, managing, and monitoring compliance practices at the process owner-level. Proactively making compliance everyone’s business is essential to maintaining leadership and protecting global brand while balancing the pressures of current and future compliance regulations.

You can also download a PDF version of this whitepaper (13 pages).

Table of Contents

Universal Compliance Challenges

The Mixed-Mode Problem: Disjointed Paper and Electronic Communications

The Inaccessibility Problem: Impenetrable Information Silos

The Coordination Problem: Cross-departmental Collaboration

Taking a Cultural Approach: Transforming Compliance Challenges From Burden to Enabler

Focus on People: Shared Understanding and Transparent Adoption

Focus on Process Management: Automation and Information Accessibility

Focus on Technology: Infrastructure for “Beyond Compliance”

Compliance Cultures in Action: Financial Services

The Challenges of Broker-Dealer Information Management

Understanding the SEC 17a Mandates

SEC Compliance Expectations

Case Study: Focus on a Leading Global Investment Bank

Conclusions: The Gilbane Group Perspective

Highlighted Company Contact Information

Appendix A: Industry Resources

Appendix B: Educational Resources

Executive Summary

Every organization, regardless of size or market, shares a common set of goals: to generate and grow revenue, satisfy customers, and operate at optimum levels of efficiency. In recent years, executives and boards of directors have put another critical directive on the plate for management: regulatory compliance ranging from SEC to Sarbanes Oxley to HIPAA mandates.

These regulatory requirements are daunting. The number and scope of worldwide laws, regulations and standards is staggering and continues to expand. Many regulations are complex, subject to interpretation, and lack best practices. Overlay geographic and industry-specific regulatory environments, and it’s easy to understand the frustration and concern within all global companies.

Implementation deadlines and audits as well as high-profile prosecutions and litigations have created a “culture of fear” in organizations that is counter-productive to standard corporate goals. Combating the fear factor requires a certain amount of simplicity. The core issue underlying compliance is surprisingly clear:

Focus on the lifecycle of paper and electronic communications –

how information is created, routed, managed, accessed and archived.

Granted, a minimal definition does not translate into a universal approach for addressing regulation mandates. What it does provide, however, is one of the best tactics for transforming a culture of fear into a culture of compliance – an environment in which cross-department process owners have:

- A shared understanding of the organization’s compliance practices.

- Simplified and non-disruptive business processes.

- Ubiquitous and transparent technologies that support these processes.

The objective of this whitepaper is not to concentrate on if, when, or how much money organizations should spend on compliance. Organizations are already responding with dollars, spending $27.3 billion in 2006 ($9 billion in technology) to support compliance programs, according to AMR Research. The more apt discussion for compliance program strategies is “how can the investment result in both compliance and corporate benefit?”

Many organizations have significant and widely-reported concerns about the usefulness of compliance costs, particularly with regulations such as Sarbanes-Oxley. Due to the omnipresent fear factor, a significant percentage of these investments have been reactive, “fire-drill” approaches that inevitably become fragmented, misunderstood, and underutilized by process owners.

Establishing a culture of compliance relies on persistent, proactive risk management. It encourages organization to:

- Assess information lifecycle requirements in the context of the people and processes closest to the documents, faxes, e-mails, and records in question.

- Balance compliance mandates for accessing, sharing, and storing information with these requirements.

- Insert specific content technologies such as version control, document routing, and archiving directly into these processes.

This approach provides a foundation for a culture of compliance that tangibly contributes to standard corporate goals for revenue, customer satisfaction, and efficiency.

Universal Compliance Challenges

In general, most worldwide, geographical, and industry-specific laws and regulations have a strong focus on how organizations manage paper and electronic communications in the context of specific business processes. Addressing this issue requires organizations to adapt or reengineer certain processes at strategic and tactical levels to ensure the following quality-driven criteria:

- Accountability

- Information accessibility

- Information accuracy

- Information integrity

- Security

- Standardization

Achieving these criteria poses a set of challenges common to all organizations, generally categorized by the ability to successfully integrate the requirements of people, business processes, and technology. In other words, how can process owners execute and manage non-disruptive, usable and repeatable processes that support compliance practices? How can compliance processes become, in the words of the IT Compliance Institute, “an everyday, network-enabled, front-office habit?” How can organizational strategies account for the current regulations as well as inevitable future ones?

The universal challenges of compliance must also be balanced and coordinated with the expectations of most regulatory agencies for a “compliance program lifecycle.” This is a tall order for any organization regardless of industry. However, understanding the common themes within compliance challenges can help focus organizations directly on the pain points that plague even the best efforts of compliance officers and implementation committees.

The Mixed-Mode Problem: Disjointed Paper and Electronic Communications

The need to focus on the paper and electronic communications lifecycle has increased significantly over the past five to ten years. One of the more significant drivers has been the multi-faceted impact of global economies, compelling organizations to:

- Increase presence and revenue through expansion

- Protect brand through standardization and localization

- Operate efficiently through centralized controls with distributed capabilities.

Paper and electronic communications are an integral part of achieving each of these corporate mandates. Naturally, the volume of communications grows exponentially as an organization increases its size, product lines, and global footprints. However, business processes that drive paper and electronic communications are often distinct and uncoordinated in many organizations.

Because compliance has an inherent focus on communications – internal, with partners, and most importantly, with customers – the corporate commitment to aligning business processes for paper and electronic communications becomes crucial to achieve well-coordinated and widely adopted compliance practices. Eliminating risk exposure often means compliance at the communications’ entry and exit points across the organization.

For example, in the financial services industry it is unacceptable to have unmonitored fax machines and e-mail systems that allow anyone to send or receive information without a formal record of the transaction. It is unrealistic to anticipate achieving compliance with regulations such as the Securities and Exchange Act (SEC) of 1934 and its amendments with this type of paper and electronic communications gap.

Regulatory focus on paper and electronic communications as well as defining what constitutes a “record” will only increase in the future. As of May 2003, Enterprise Storage Group researched more than 10,000 laws and regulations in the United States alone drafted by federal and state legislative bodies. The common thread? Addressing all forms of “records information.”(1.)

The Inaccessibility Problem: Impenetrable Information Silos

In addition to the always-on Internet, the ubiquitous availability of content technologies, including e-mail, brings the ability to communicate, publish and share information to an unprecedented number of individual contributors. In essence, everyone’s a publisher, which is good and bad news. Ease-of-use means that “publishing” rarely requires training and is enabled from the desktop. On the other hand, “no training required” usually equates to the absence of formalized policies and procedures and more importantly, governance where appropriate or mandated.

Despite the increase in document, content, and e-mail management system implementations over the past five to eight years, a 2003 PricewaterhouseCoopers estimated that the average organization makes 19 copies of each document, misplaces 1 out of every 20 documents, and spends $120 in labor searching for each misfiled document. Furthermore, the vision of the paperless office is far from reality. In fact, according to authors Abigail Sellen and Richard Harper, the use of e-mail in an organization increases paper consumption by an average of 40 percent.(2.)

It is important to understand, however, that the management of paper and electronic communication is not the only problem to solve. In fact, when regulatory examiners arrive at the door, the accessibility to information usually poses the more formidable problems.

The Coordination Problem: Cross-departmental Collaboration

Organizational coordination and collaboration issues increase significantly as corporations strive for new or increased revenue by expanding global operations. This has an analogous effect when viewed in the light of compliance laws and regulations. As more process owners “get into the mix” of business processes for revenue generation and customer satisfaction, many will need to understand and be intrinsically involved in compliance practices.

Corporate reactions to compliance issues have resulted in centralized compliance departments, more significant oversight from legal departments, and IT-based compliance specialists. This is a strong and practical trend. However, it does not replace the need for executive-level support for compliance practices. Naturally multi- and cross-departmental, the lifecycle of paper and electronic communications usually contains uncoordinated “gaps” and a lack of cross-functional, shared understanding.

Enterprise education cannot be overlooked either and requires involvement and commitment from training, documentation, and human resources departments. Of course, determining the right level of individual and departmental involvement in compliance strategies versus implementations versus daily practices is warranted. Without coordination and collaboration, however, the adjective “underutilized” quickly comes to mind.

Taking a Cultural Approach: Transforming Compliance Challenges From Burden to Enabler

Tackling compliance challenges requires a proactive, consistent and realistic strategy to achieve transparent risk management: the ability for global business managers to seamlessly incorporate compliance policies and practices into daily business processes. A culture of compliance puts strong emphasis on people along with the valuable, but inevitable focus on business processes and technology.

This three-tiered approach to corporate strategy is certainly not new. Given the range of non-compliance prosecutions, however, the “people, process and technology” mantra is often lost in corporate reactions to compliance challenges. In reality, the mantra is significant to ensuring successful programs and daily practices. Compliance laws and regulations require corporate commitment, individual understanding, and most importantly, enterprise-wide adherence. It is unrealistic to achieve these requirements without a comprehensive approach.

Getting “back to basics,” i.e., the standard corporate goals such as revenue-generation, customer satisfaction, and efficiency is also a core part of a culture of compliance. In fact, compliance programs can actually be worth the effort according to the General Counsel Roundtable, who reports that on average, $1 spent on compliance saves $5.21 “in heightened avoidance of legal liabilities, harm to organization reputation and lost productivity.”(4.) Viewing compliance strategies from this perspective can transform adherence from a fear-driven cost burden to an enabler for:

- Brand protection

- Risk management

- Business continuity

- Cost savings and productivity increases

Focus on People: Shared Understanding and Transparent Adoption

Many organizations report that the most difficult compliance challenge is not necessarily devising policies, procedures, and governance programs, but rather ensuring they are adopted. At its core, compliance is about the lifecycle of paper and electronic communications and records – how information is created, routed, managed, accessed and archived. Obviously, process owners perform these tasks throughout this lifecycle on a daily basis.

Fragmented, uncoordinated processes that are individualized or department-specific are never consistent and always redundant. This lack of collaboration – and at its core, a lack of shared understanding of lifecycle processes – increases the risk of non-compliance and the likelihood of prosecution.

A culture of compliance has a strong emphasis on people, particularly focusing on:

- Providing documented organization mission statements, policy and procedure manuals, and educational tools that help process owners understand “how they fit into the picture”

- Establishing a “business-neutral” compliance officer and cross-departmental compliance team (i.e., executives, business process owners, IT, and administrative personnel) that has detailed knowledge of industry or process-specific regulation requirements.

- Implementing non-disruptive content technologies that transparently integrate with familiar desktop or networked software and hardware. (For example, it is unrealistic and impractical to eliminate common communications tools such as fax and e-mail.)

- Mentoring, or in the financial industry’s terms “chaperoning”, new personnel that need to ramp-up on how regulations affect their responsibilities.

The simple fact is that policies, procedures, and the technology that supports them do not work if they are not accessible, flexible and usable for the people they serve. They can certainly be implemented, but there’s little guarantee they will be used without these characteristics.

Focus on Process Management: Automation and Information Accessibility

A culture of compliance enables process owners to “work smarter” by emphasizing automation techniques for manually-intensive tasks to eliminate redundancy and inconsistency. The paper and electronic communications lifecycle contains numerous opportunities for process automation, including:

- Metadata population – to enable all forms of process automation

- Production – to ensure brand and format consistency and quality

- Indexing – to prepare for easy access during regulatory examinations

- Routing and Distribution – to inject security, intelligence, and consistency into communications delivery

- Archival – to store hardcopy and/or digital communications as appropriate

A culture of compliance also has a strong focus on information accessibility, creating an environment where process owners can quickly search, retrieve, and deliver information as required by a particular regulation or audit. For example, identifying the full “chain of events” is particularly significant during financial services audits that focus on broker-dealers and transfer agents. However, many organizations report difficulties in complying with discovery orders because content is not managed or archived in a way that enables timely search and retrieval.

This is clearly not acceptable to organizations such as the SEC, who stress prompt response for broker-dealers: “We expect that a fund or adviser would be permitted to delay furnishing electronically stored records for more than 24 hours only in unusual circumstances. At the same time, we believe that in many cases funds and advisers could, and therefore will be required to, furnish records immediately or within a few hours of request.(5.)”

Focus on Technology: Infrastructure for “Beyond Compliance”

A culture of compliance enables organizations to get “back to basics” in terms of enterprise-wide focus on standard corporate goals such as revenue generation, customer satisfaction, and efficiency. To do so, content technologies applied to compliance challenges must deliver an infrastructure that facilitates both short and long-term process improvement.

Looking beyond regulatory compliance should be core to any technology-driven compliance solution, characterized by the solution’s applicability to other business initiatives and applications. Compliance solutions must demonstrate “platform-centric” capabilities such as:

- Strong workflow – promotes the process automation factors described in the previous section; enables better allocation of resources.

- Security – provides the architecture to protect against unauthorized access to or use of information at the individual, role, and group levels.

- Auditing and reporting –promotes a “checks and balances” for reviewing current practices; provides the ability to readjust as necessary.

- Distributed architecture – enables organizational and geographic flexibility with centralized control.

- Integration – integrates with document, content, records and/or e-mail repositories, storage and archival systems, and communications-driven hardware devices.

- Scalability – accounts for growing volume in paper and electronic communications as well as increasing numbers of process owners and contributors. In a large financial services organization, for example, it is not unusual to have 1,000+ distributed multi-function devices supporting communications processes such as scan to fax.

- Performance – delivers high availability and reliability through techniques such as clustering, load balancing, redundancy and failover.

Compliance Cultures in Action: Financial Services

According to a Securities Industry Association (SIA) 2006 survey, the cost of compliance in the U.S. securities industry reached more than $25 billion in 2005, up from $13 billion in 2002(6.). SIA defines the broad definition of compliance costs as a “firm’s overall efforts designed to achieve compliance with all applicable laws, rules, and regulations, and supervision and surveillance requirements.(7.)”

The critical issues of data integrity, authenticity, and management affects a broad audience in the financial services industry including securities firms, investment banks, stock brokerages, hedge funds, mutual funds, investment advisors and other financial institutions that deal in securities trading. Given rising global competition and cross-border mergers in this arena, achieving successful compliance programs in the financial services industry often poses unique challenges.

A lack of awareness and misunderstanding of compliance issues is costly to say the least. The most popular citation in compliance “fear factor” discussions is the December 2002 SEC $8.25 million fine applied to five of the largest investment banks in the world for failing to follow document retention policies. Brand name organizations included Goldman, Sachs & Co., Citigroup Inc.’s Salomon Smith Barney, Morgan Stanley & Co., Deutsche Bank Securities Inc., and U.S. Bancorp Piper Jaffray Inc. Non-compliancy issues ranged from laws and regulations specified in the SEC’s Rule 17a-4, the NYSE’s Rule 440, and NASD’s Conduct Rule 3110.

In May 2005, Morgan Stanley was in the spotlight yet again because the company could not guarantee it had turned over all e-mails related to a lawsuit filed against by financier Ronald Perelman. This resulted in a $1.58 billion judgment awarded by a Florida jury against the company, subsequently followed by $15 million SEC fine a year later. Undoubtedly, doing nothing or “fire-drill” approaches to litigation risks and compliance regulations has severe consequences.

A proactive culture of compliance that emphasizes people, process and technology management is particularly relevant in this industry. Based on non-compliance prosecutions, it is clear that even the best solution implementations and automation techniques will not help if:

- The incentive for the compliance program is more concerned with job security than process improvement

- The compliance officer has limited authority

- There is little commitment from senior management

- There is resistance from process owners

In addition, one of the most significant roadblocks to adherence is a shared understanding of what regulations mean in the context of particular business processes. In fact, the response to a SearchStorage.com poll on SEC regulations such as SEC Rule 17a-4 revealed that 59% of respondents did not know whether they were in compliance “simply because they just can’t figure out what specifically they have to do.”(8.)

The Challenges of Broker-Dealer Information Management

As the saying goes, “hindsight is 20/20.” For broker-dealers, transfer agents, and financial advisors however, the goal of a culture of compliance is foresight, including:

- Preventing violations from occurring

- Detecting violations that have occurred

- Promptly correcting any violations that have occurred .(9.)

- Avoiding financial penalties and reputation damage

In turn, the SEC has high expectations for managing the paper and electronic communication lifecycle as well as safeguarding it. For example, even though many employees in financial organizations are not involved in a firm’s transactional operations, the range of “access persons,” i.e., employees that may come into contact with material, non-public information, is increasing due to global operations. In turn, there is a heightened SEC focus on systematic management, safeguarding, and security.

Understanding the SEC 17a Mandates

Laws and regulations for the lifecycle of paper and electronic communications are at the heart of the SEC’s Rule 17a-3 and 17a-4 amendments to the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. Specific to communications among broker-dealers and their clients, it includes all hardcopy documents mailed, faxed, or delivered in person as well as electronic communications delivered by e-mail or through the Web. It also stresses the preservation of original appearance.

In general, the 1934 Act is a set of laws requiring records to be made and kept for the purposes of review and auditing of securities transactions. It was designed to protect investors from fraud by ensuring proper, fair and transparent practices in the buying and selling of securities. The Rule 17a series, originally proposed in 1996, was designed to implement expansive books and records reforms for the lifecycle of paper and electronic communications, including:

- Written and enforceable retention policies

- Storage of data on indelible, non-rewriteable media

- Searchable index of all stored data

- Readily retrievable and viewable data

- Storage of data offsite

The amendments spawned numerous concerns and formal comment letters from the financial services industry related to interpretation, cost, and feasibility. However, all parties seemed to embrace the overall themes driving the amendments, namely information availability, accuracy and completeness. The rules were issued as a final release in November 2001, with an effective date of May, 2003.

|

Rule |

Focus |

Includes mandates and guidance on: |

|

17a-3 |

What records need to be saved |

|

|

17a-4 |

How records need to be saved |

General procedures and retention requirements with a strong focus on preserving in an accessible manner, specifically:

|

Appendix A: Industry Resources, provides information on specific laws and regulations in the financial services industry.

SEC Compliance Expectations

As discussed previously, the SEC has high expectations for information accessibility. For example, under Rule 17a-4’s retention specifications, search indices must be maintained in conjunction with actual records. Obviously, electronic archival and storage is useless without categorization, indexing, search and retrieval technologies. In general, examiners expect prompt information access and delivery on the same day or within 24 hours. Additionally, if organizations respond that production will not be “prompt,” examiners expect that organization will:

- Inform them of the delay and its cause,

- Provide them with a schedule for the delayed production

- Meet the milestones in the schedule

It is inevitable that regulatory pressures will continue, requiring firms to adopt clear compliance policies and implement systems to support these policies. Institutions such as the Center for Public Company Audit Firms (AICPA), the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), and the Securities Industry Association’s (SIA) Compliance and Legal Division are responding with guidance and best practices information. Resources to specific programs and documents can be found in Appendix B: Educational Resources.

Case Study: Focus on a Leading Global Investment Bank

Many corporate approaches to the SEC 17a mandates focus on e-mail, instant messaging archiving, and electronic classification and indexing. While this approach is prudent and necessary, numerous organizations neglect emphasis on traditional communication methods such as paper and fax-based communications. To deliver a 100% compliant solution, global financial services organizations must understand and address the “mixed-mode problem,” i.e., disjointed business process for paper and electronic communications.

In the following case study example, a leading global investment bank realized their current fax infrastructure fell short of meeting its compliance obligations of tracking and recording all customer communications regarding investments. As a result, the investment bank replaced its use of fax machines throughout the company with an alternative solution provided by Omtool, Ltd. and Hewlett-Packard. The solution allows employees to send and receive hardcopy documents via fax in a way that meets the compliance obligations of SEC 17a-3 and SEC 17a-4.

The solution replaced enterprise-wide fax machines with systems from HP; specifically the HP Digital Sender 9200 and the HP 4345 MFP. These devices now enable users to continue sending documents via fax while capturing and integrating communications with the company’s archive system.

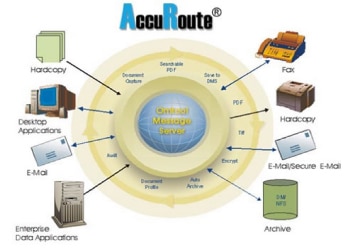

The transparent integration between AccuRoute and HP MFPs empowers process owners with a “single purpose” user interface at the device level. In essence, users press one button on the control panel of the device and the document is immediately faxed. Behind the scenes, the solution automatically:

- Routes faxes through the Omtool AccuRoute server

- Records the identity of the sender and recipient

- Captures and indexes a copy of the document.

- Transfers the document to the bank’s e-mail tracking and archive system.

The following steps describe the workflow in this approach:

|

Culture of Compliance:

|

|

Conclusions: The Gilbane Group Perspective

Compliance issues have created a culture of fear in many organizations that is counter-productive to revenue-generation, customer satisfaction, and efficiency. Committing to a culture of compliance eliminates the fear factor, enabling corporate-wide adoption and shared understanding.

When organizations and technology vendors collaborate with these principles in mind, the effect is significant. Such is the case with the partnership between Omtool, Ltd. and Hewlett-Packard, in which content technologies seamlessly work together to deliver an infrastructure that addresses compliance challenges in the financial services industry. As demonstrated in the case study, the result delivers transparent risk management, makes compliance everyone’s business, and enables a leading global bank to get back to corporate basics.

1. Briggs, L, “ Paper Cuts: Scanning Makes a Compliance Comeback,” June 2005, http://www.itcinstitute.com/display.aspx?id=361

2. Gerr, P., Babineau, B., and Gordon, P. “ Compliance: The effect on information management and the storage industry “ May, 2003. The Enterprise Storage Group

3. Harper, R. and Sellen, A., “The Myth of the Paperless Office” MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 2003

4. Corporate Executive Board, General Counsel Roundtable. “Seizing the Opportunity, Part One: Benchmarking Compliance Programs,” 2003. http://www.generalcounselroundtable.com

5. Securities and Exchange Commission. Electronic Recordkeeping by Investment Companies and Investment Advisers, 17 CFR Parts 270 and 275,” May 2001. http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/ic-24991.htm

6. S. Carlson, “The Cost of Compliance in the U.S. Securities Industry: Survey Results,” February 2006. http://www.sia.com/surveys/pdf/CostofComplianceSurveyReport.pdf

7. S. Carlson and F. Fernandez, “The Cost of Compliance in the U.S. Securities Industry,” February 2006. http://www.sia.com/surveys/pdf/CostofComplianceSurveyReport.pdf

8. Evans-Correia, K. “Businesses fail to meet SEC rules on e-mail archiving, risk fines, imprisonment,” April 2003. http://searchstorage.techtarget.com/originalContent/0,289142,sid5_gci891711,00.html

9. Securities and Exchange Commission. Compliance Programs of Investment Companies and Investment Advisers, 17 CFR Parts 270 and 275,” December 2003. http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/ia-2204.htm#P214_79016

Highlighted Company Contact Information

For more information please contact:

|

Karen Cummings, EVP Marketing |

Joseph Wagle, Financial Services Solutions Manager |

|

6 Riverside Drive |

3000 Hanover Street |

|

Andover, MA 01810 |

Palo Alto, CA 94304-1185 |

|

(800) 466-8665, ext 5707 |

212.350.6736 |

|

Kcummings@omtool.com |

joseph.wagle@hp.com |

Appendix A: Industry Resources

There is a constantly-changing landscape of compliance regulations that affect the financial services industry, with particular focus on broker-dealer information management. The following table provides an overview of the major regulations.

|

Regulation |

Description |

|

Bank Secrecy Act of 1970 |

Designed to prevent financial institutions from being used as intermediaries for the transfer or deposit of money derived from criminal activity and to provide a paper trail for law enforcement agencies in their investigations of possible money laundering. Updated with AML (Anti-Money Laundering) provisions as a result of USA PATRIOT Act of 2001, Title III (International Money Laundering Abatement and Anti-Terrorist Financing Act of 2001. Specifically requires every financial institution to establish an AML program, subject to audit. |

|

European Commission’s Directive on statutory audits |

Broadens the scope of the Eighth Council Directive on Company Law and establishes international co-operation between EU regulators and other countries such as the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/auditing/directives/index_en.htm |

|

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 |

Focuses on provisions to protect consumers’ personal financial information held by financial institutions. Eight federal agencies and the states have authority to administer and enforce the Financial Privacy Rule and the Safeguards Rule. Both apply to banks, securities firms, insurance companies, and companies that provide financial products and services. |

|

National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) |

Conduct Rule 3010 and Conduct Rule 3110 mandate that that members retain correspondence of registered representatives relating to investment banking or securities and make and preserve books, accounts, records, memoranda and correspondence in conformity with all applicable laws, rules, regulations and statements as prescribed by SEC Rule 17a-3 and SEC Rule 17a-4. |

|

New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) |

Rule 440: Books and Records mandates that every member not associated with a member organization and every member organization shall make and preserve books and records as the Exchange may prescribe and as prescribed by SEC Rule 17a-3 and SEC Rule 17a-4. |

|

Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 |

Section 103 mandates that accounting firms must retain records relevant to the audit and financial statement review functions for seven years. |

|

Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, specifically Rule 17a-3 and 17a-4 |

Covers overall record keeping for the financial services industry including policies, procedures, customers, accounts, correspondences, transactions, and even contemplated transactions. Includes mandates for maintenance, storage, monitoring, and accessibility. Includes specific regulations for paper and electronic records capture, management, and archival. |

Appendix B: Educational Resources

This section provides references and links to publications that assist financial services organizations in understanding auditing procedures, standards, and advice on best practices. Although not all-inclusive, the following table provides compliance officers with valuable educational resources.

|

Organization |

Publication |

|

Canada ’s Centre of Excellence for Internal Audit |

Provides internal audit policies and guidance – http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/ia-vi/home-accueil_e.asp |

|

Center for Public Company Audit Firms (AICPA) |

Provides general resources – http://cpcaf.aicpa.org / Note: Also includes the publications PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 2: A Guide for Financial Managers and Internal Control Reporting and Implementing Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404, Revised Edition |

|

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) |

Publishes The Enterprise Risk Management — Integrated Framework (2006) – http://www.coso.org/publications.htm |

|

European Commission |

Provides recommendations and communications – http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/auditing/ |

|

European Corporate Governance Institute |

Provides the Working Paper Series in Finance http://www.ecgi.org/wp/ssrn_downloads.php?series=Finance |

|

Government Accountability Office (GAO) |

Publishes the GAO Auditing Standards 2006 Revision – http://www.gao.gov/govaud/ybk01.htm. Also provides a list of auditing organizations – http://www.gao.gov/aac/auditingorganizations.htm |

|

Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) |

Provides guidance information and publications such as Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404: A Guide for Management by Internal Control Practitioners and Corporate Governance and the Board – What Works Best http://www.theiia.org/index.cfm?doc_id=118 |

|

International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) |

Provides independently-developed standards on auditing, quality control, review, and other assurance and related services – http://www.ifac.org/iaasb/ |

|

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) |

Provides a general overview of and guidance on records management through ISO 15489-1 and 15489-2 – www.iso.org |

|

North American Securities Administrator’s Association (NASAA) |

Provides investor protection as an international organization since 1919 and participates in multi-state enforcement actions and information sharing. Coordinates and implements training and education seminars – http://www.nasaa.org/industry___regulatory_resources/ |

|

National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) |

Publishes all rules and regulations along with the NASD manual – http://www.nasd.com/RulesRegulation/index.htm. Also offers the CRCP certification program (Certified Regulatory and Compliance Professionals) in conjunction with the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania –http://www.nasd.com/EducationPrograms/NASDInstitute/index.htm |

|

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) |

Publishes PCAOB standards –http://www.pcaobus.org/Standards/index.aspx |

|

Securities Industry Association (SIA): Compliance and Legal Division |

Provides educational materials and seminars on compliance issues – http://www.siacl.com/ |